Who’s Getting Into America’s Painkillers?

Until the late 1990s, painkillers were sparingly handed out by doctors and dentists. After serious injuries or surgery, you might be given a short course of morphine or another opioid pain reliever. But they were truly serious injuries—not sprained ankles or chronic low back pain. Doctors considered these drugs too addictive to put people on for a long term, unless they were at the end of their lives. But now, with these drugs being used so much more freely, there are more painkillers in circulation to be used—or misused—by anyone in America’s households. Too often, the person misusing these drugs is NOT the original patient.

How the Problem Started

In 1996, Purdue Pharma, patent-holders of a new, extended-release formula, made a dramatic change in their marketing. They expanded their sales teams and indoctrinated them with a new message: This new formula of extended-release OxyContin is not likely to be abused and can be given to patients without concern for addiction.

Purdue Pharma management knew that these messages were false—as they admitted in 2007 in federal court. But instead of distributing correct information, they heavily rewarded their sales staff for higher prescribing numbers by the doctors they courted. Just about any tactic was acceptable as long as the sales figures went up. And when doctors accepted the idea that they could finally relieve pain without addicting their patients, they were ready to write the prescriptions.

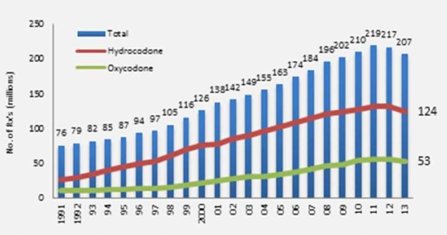

In the chart above, you can see just how successful these tactics were. Follow the green line to see the increases in oxycodone sales (that’s the painkilling ingredient in OxyContin). The total number of prescriptions for these two painkillers hits more than 200 million per year. And there are additional opioids not represented on this chart.

What this means is that tens of millions of households now have half-full bottles of these painkillers in their medicine chests. For most people, a few days of a painkiller is all that is needed after a minor injury or dental work. As a result, the people getting into these bottles are often not the intended patient.

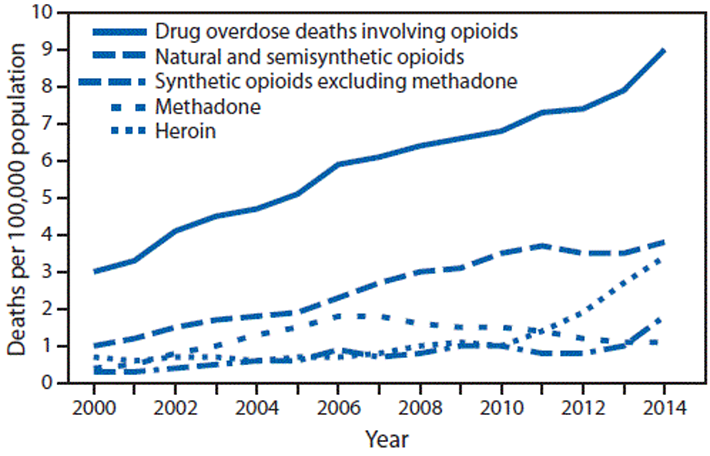

A New Report on Opioid Poisoning

It’s called “opioid poisoning” when someone gets into these pills and gets sick and needs to be rushed to the hospital. And according to a new report, the primary groups being exposed to this poisoning are toddler and teenagers. As one of the authors of this new report pointed out, enough pills are being prescribed to put a bottle in every household.

These researchers found that the number of children hospitalized due to opioid poisoning more than doubled over a 16-year period. Per 100,000 children, the number went from 1.40 to 3.71. But for toddlers alone, the number more than tripled. That is because, of course, toddlers will put anything they find in their mouths.

But teens also had very high risk of opioid poisoning. In 2012, more than ten teens per 100,000 were hospitalized for opioid poisoning. In their case, their exposure is due to factors like curiosity or a desire to self-medicate some emotional or physical problem.

A Need for Greater Awareness and Secure Storage

Many families believe that drug abuse or addiction will not strike their home. Parents may also be reluctant to show their teens that they don’t trust them by locking up medications. But until opioids are distributed by doctors in an extremely constrained manner, it’s vital to keep these surplus pills out of reach—and under lock and key.

Toddlers may want to imitate mom and dad by chewing on a couple of pills or think they are candy. Teens may want to find out what all the furor about these pills is all about. In between these ages, children are old enough to know they should not consume those pills and not old enough to be curious about the effects of the drugs.

It could also happen that the one who samples these pills is not even a child. A family member, teenaged visitor, a construction worker or even someone who comes to look at the home for purchase could feel an urgent need for more pills. Locking up these pills keeps them out of all these hands.

Locking medicine chests are easily found online or in home improvement stores. Locking medicine bags or boxes are also easy to find. A modest investment could save a loved one from drug abuse, addiction or even overdose death.